You might be confusing the marketplace about what products and services your company offers without even realizing it. Many companies that have been in business for a long time, especially those that have grown over the years through acquisitions, gradually become a multi-layered mix of new and legacy brands, each with their own brand identities. This can perplex consumers—and make them less willing to buy.

However, it’s not always easy to sense this confusion from inside your company, because you’ve grown accustomed to how things are and you may not have a clear view outside your walls.

In this post, we’ll look at the main types of brand architecture models, and how the structure of your brand can prevent problems like this. We’ll examine the benefits of solidifying a brand architecture and some considerations for when you do it. Finally, we’ll consider why a neutral third-party can bring a ton of value to a brand consolidation.

What is brand architecture?

The short version is that a brand’s architecture is a way of organizing the different subsections of a larger brand. Brand architecture shows us how the sub-brands of a larger whole are organized, and how they all relate to each other. It can help a marketer see how to keep parts of a brand separate when needed, and also how to allow them to work together to boost one another in the marketplace.

Let’s look at some brand architecture examples to see how this works.

Types of brand architecture

There are three main types of brand architecture models: the branded house, the house of brands, and the endorsed brand. Each option comes with its own advantages and disadvantages.

The Branded House

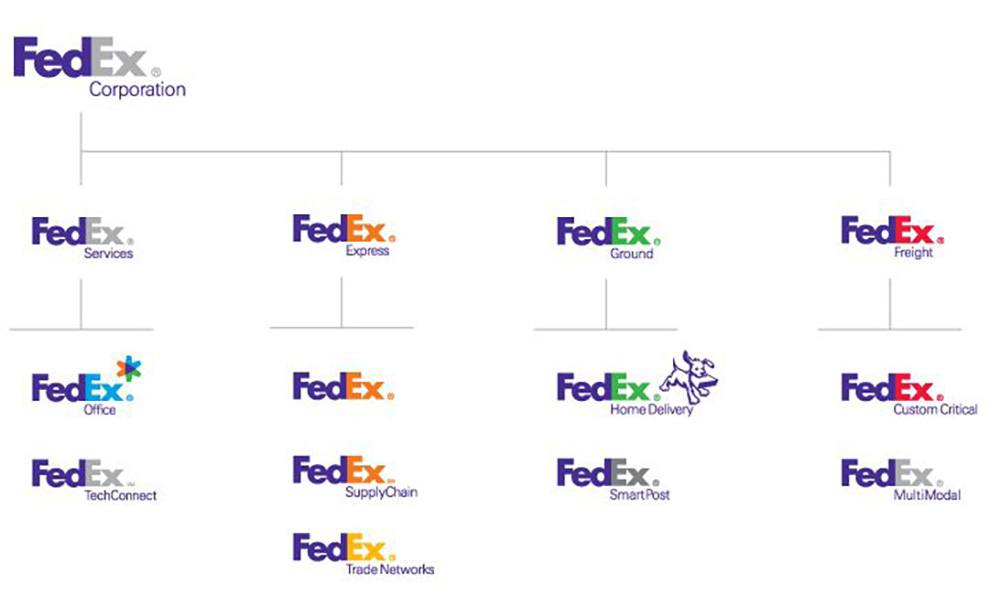

In the branded house, a parent brand—typically one with some clout—runs the show. All of the sub-brands are subordinate to the parent brand, and they usually will share a name with a qualifier to explain exactly what that sub-brand does.

FedEx is one example of the branded house brand architecture model, with their operating companies and portfolio of solutions all falling under the name of the master brand. This structure makes for a consistent experience, minimizes confusion, and builds equity for the corporate brand.

The House of Brands

The house of brands is basically the opposite of the branded house. There’s a parent brand, but it’s not reflected in the sub-brands in an obvious or blatant way. In fact, often the parent brand is in the background, overshadowed by one or more of its sub-brands. You’ll see this brand architecture model more in situations where a holding company buys up subsidiaries—to most consumers, the parent is irrelevant compared to the individual products that it distributes.

One brand architecture example for the house of brands is Procter & Gamble, with dozens of product brands underneath the parent P&G brand. This structure makes sense for P&G due to its large number of products, many of which have been marketed for decades under the product name. Changing the name of something like Crest to match the Procter & Gamble parent brand would only serve to confuse loyal consumers—this way, P&G retains the brand equity of all their products.

A house of brands might also be something of a hybrid, where one of the “sub-brands” is also the parent. Think about Coca-Cola. Coke itself and Diet Coke (and Coke Zero, etc.) obviously share their name with The Coca-Cola Company. But Sprite and Tab and Fanta do not, nor does Dasani bottled water. Obviously a closer look at the packaging reveals the connection, much like a P&G product would. But the next can of “Coca-Cola Lemon-Lime” I see will be the first.

The Endorsed Brand

An endorsed brand sort of meets in the middle of the other two brand architecture models. A parent brand does form an umbrella over a host of other related brands, much like in the house of brands, and the related brands aren’t necessarily going to share a name with that parent like in the branded house. But in the endorsed brand model, the parent brand plays a much bigger role in the children’s lives than in the house of brands.

Marriott is an example of a hybrid brand structure where some brand extensions feature the parent name, while others do not. This format provides flexibility in naming and brand building. However, some consumers may be unaware of the connection between the master brand and companies that carry a different name (between Marriott and Sheraton, for example).

In recent years, many companies have been moving toward a strategy of emphasizing their corporate brand name over individual products. While the efficiency of this approach can be appealing, it doesn’t prioritize customer segmentation, Harvard Business Review notes.

Choosing which one of these types of brand architecture is right for your company involves considering factors such as your current architecture, your marketing goals, your current product/services mix, and new products in your pipeline. You also need to take into account the experience of your customers. For example, your print materials might clearly describe your solutions, while your website might be a maze to navigate. (That’s something that can be evaluated with platforms like Google Analytics.)

Moving to a new type of brand architecture isn’t something to be taken lightly, as it can involve everything from a new messaging strategy to redirecting legacy websites. However, the benefits of building a consistent architecture are considerable.

Benefits of a consistent brand architecture

Let’s imagine that your company has performed a number of acquisitions over the years, and that those acquired companies don’t necessarily have the same brand personality as the parent organization. This can translate into any number of issues for customers. For example, when the customer clicks on a specific solution on your website, they might be taken to a different web domain that looks and feels quite different, which is confusing—they might even think the link is broken, or that they accidentally clicked on an ad. Or a prospect might bounce from your site because the hierarchy of information isn’t intuitive.

Acquisitions can be a very emotional process. Often, the acquiring company goes out of its way to make the new company feel welcome; while this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, in some cases the acquired company never gets fully consolidated and ends up operating as a sort of rogue unit with a brand that sticks out like a sore thumb.

So what are the benefits of a stronger type of brand architecture and unified brand? These are just for starters:

Gain clarity in the marketplace

Instead of a portfolio of companies that look and sound different, you’re able to emphasize their connection through a consistent visual and verbal identity. Better yet, that clarity can increase the confidence of your board of directors, VCs, and other stakeholders.

Grab attention with a bold story

Every company has a story to tell, but sometimes the compelling aspects of that story are buried. Consolidating your brand gives you the opportunity to tell why you’ve built your company—what unites you, what unique capabilities you’ve developed, and why you came together the way you did. Telling that story the right way will require research, synthesis, a communications strategy, and creative execution.

Grow revenue through cross-selling

When you clearly articulate your story, you’re able to express the full value of your combined solutions—how they complement each other. That makes it easier to cross-sell across business units.

Create a more inclusive culture

A compelling unified story can serve as a rallying cry for all your employees, one that makes everyone in various business units and locations feel like they’re all fighting for the same cause. That’s why it’s important to plan the internal launch when you’re working on a new brand: to create an authentic buzz before the external launch.

Considerations for a brand consolidation

Consolidating brands isn’t something that can be done overnight. It takes sustained effort involving research, synthesis, strategy, and execution. This can involve:

- Customer/prospect interviews to tell you what they value and how they view the market and your company

- A discovery session and internal interviews to discern what executives, subject matter experts, or other key stakeholders think you should be saying

- A communications audit to determine how you’re currently communicating to the marketplace

- Competitor research to understand the brand structure of your competitors and how they’re communicating

- Creation of strategies for communications, as well as the internal and external brand launches

The case for hiring a neutral party

In many cases, a marketing agency can bring great value to a brand consolidation project. They can serve as an impartial observer who asks important questions and makes strategic recommendations without any office politics getting in the way. Also, your organization doesn’t go through a major branding project very often, while an agency that specializes in branding does numerous such projects each year, so they can bring a great deal of relevant experience.

Element Three has performed numerous branding projects over the years across different industries. Check out our branding services if you’re in need of experienced brand architects.

An expert partner can provide you with different brand architecture examples that have seen success in your industry and situation. They can do the digging to figure out which of the types of brand architecture best fits your needs, and help guide you down the right path. This way, no matter how it ends up being structured, you can be sure that there will be consistency across your brand—or brands.