As marketers, we find value in the little things—a small percentage increase in conversion rate, paid media impressions, traffic from a new channel, social media engagement, what have you. But often our excitement over these improvements fails to translate to executives and stakeholders. Why?

It’s not because we’re so smart and they don’t get it. The answer lies in what I like to call the marketing value chain—a chain we must learn and love if we want to prove the value of marketing efforts to our stakeholders.

What Is the Marketing Value Chain?

According to Investopedia, a value chain is a “business model that describes the full range of activities needed to create a product or service.” The analysis of such a chain helps to “increase production efficiency so that a company can deliver maximum value for the least possible cost.”

How’s this apply to marketing, then? The marketing value chain utilizes the same principles—describing the full range of activities in order to analyze how to increase efficiency and deliver maximum value. But instead of looking at activities to create a product or service (which would include parts, labor, processes, etc.), we’re analyzing marketing metrics.

Which marketing metrics? Well, that is a great question. The beginning of the value chain is the most variable—here, we’ll want to change things up based on the tactics we’re using to produce marketing momentum. It’s also here where you are likely most familiar—where you find your impressions, click rates, open rates, etc.

The good news is that the back of the marketing value chain almost always looks the same.

The End Is Where the Value Is

The end of your marketing value chain is where you calculate the value of your product or service. I say this is where the least variation exists because there should be some constants down here—namely, your revenue, margins, and probably even your sales pipeline (or average sales conversion rate and average sale value, for e-commerce or more B2C models).

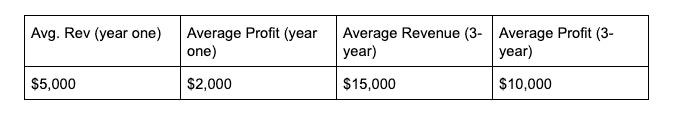

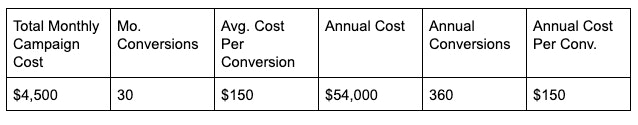

Let’s imagine a company that sells software. This software costs $5,000 annually to use, and most purchasers use the software for three years, for an average revenue of $15,000. The cost to produce the software from end to end, including marketing and sales, programming, hosting, and all of that, is higher in year one than in year three. We’ll say it’s $3,000 in year one and $1,000 each in years two and three. You now have a “metric value chain” that looks like this:

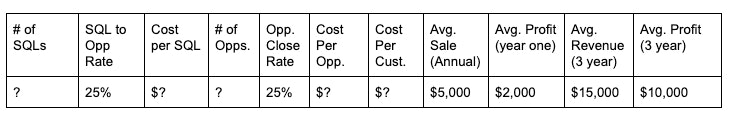

Let’s add some sales KPIs to this mix. Your software sales staff has been at it a while, and can close opportunities at a great rate, 25% of the time. Additionally, they’re equally as good at turning sales qualified leads (SQLs) into opportunities, at a 25% conversion rate. Let’s add that into our chain.

You can see where this is going. Understanding the endgame of your marketing efforts, particularly the value of a good or service sold and the metrics around sales, is very helpful in determining the value of your marketing efforts—and it’s the key for helping key stakeholders understand and get excited about your impact.

Filling In the Gaps

Your marketing efforts should be contributing to this bottom-line equation. Executives and key stakeholders are doing this math for marketing costs overall (likely with the rest of the value chain costs and profits for goods and/or services).

You become a super-marketer when you understand this back-half of the marketing metric value chain, and can connect the dots from sales, customers, and profit to your marketing tactics. Now, in the age of multitouch attribution and high-powered marketing dashboards, you may have software doing this for you already. If you do, that’s excellent (and you’ve probably been pretty bored with this so far, so feel free to skip ahead). If not, then you need something like the model above to show just how much those social media visits, ad impressions, and email opens matter.

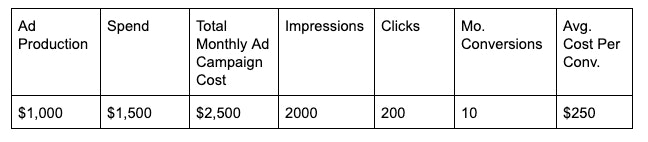

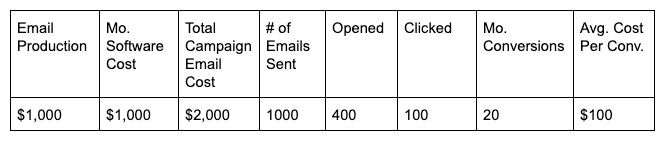

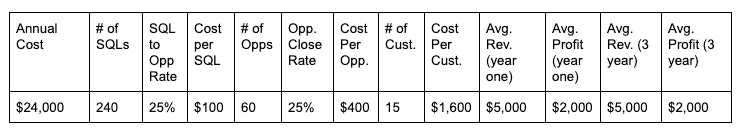

Let’s continue our example with software. Now we’re going to show the value on a demo video we’re promoting. Let’s make it easy and say anyone who views our demo is considered an SQL. We’re running ads and sending emails this month to promote the demo. We might have some marketing value chain metrics that begin like this:

Digital Ads

Email Campaign

Total Campaign

Plug those final numbers into the end of our value chain, and we get what looks like it could be a successful campaign, so long as we maintain the average lifetime value and years of use at current levels.

Why does this all matter? Well, look at how quickly that conversion you invested $150 in became a $2,400 customer. Only two steps take that initial cost to a 16-fold return. That’s why understanding the back half of the marketing value chain is important—and why no one gets super excited about your marketing metrics when they don’t add up.

Imagine two different scenarios using the same campaign results, but different situations.

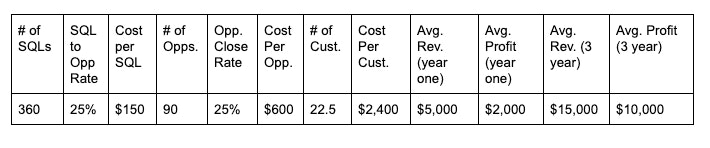

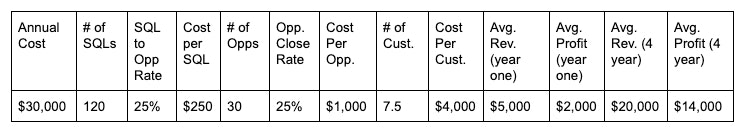

In the first, let’s say your digital ad customers stay an average of four years (adding $4k of profit to the bottom line), while your email marketing group was a bunch of bad apples who all bailed on your software after just one year. Your charts look like this, annualized:

Digital Ads

Time to think critically about our budgets. Do we want to maximize our ad spend, and invest in leads that cost more but provide longer value (e.g., spend $4,000 per customer to profit $14,000, a customer worth 3.5 times what we spent to acquire)? Or do you go for the quick wins, with a cheaper lead but less value overall (e.g., spend $1,600 to acquire a $2,000 customer—worth only a quarter more than you paid to acquire them over one year, and with no stickiness or value beyond that)?

A different scenario might see the lead conversion rate change (this would likely include sales efforts, but there’s no reason not to think of those situations too). If, in the example above, your conversion rate from opportunities to customers for email leads converted at 50%, you’re looking at $800 per customer, which makes the one-year users a little more attractive. If they stayed for two years, and you’re paying $800 for a customer that leads to $6,000 profit? Not bad at all.

The What Ifs Matter!

It may feel like you’ve fallen down the “what if?” tunnel to wonderland, but truthfully that’s where a great marketing strategist lives. If I were working as a consultant or a marketer for the above software producer example, I’d be asking all kinds of “what if” questions—around affecting open rates, click rates, conversion rates, and beyond.

Knowing the end value of marketing efforts makes it easier to determine budgets and strategies. It makes true testing valuable—this ad versus that ad, this channel versus that one—and also makes it easier to help key stakeholders understand that while some tactics may not look as attractive as others, they all play an integral role in the greater whole.

This does get a lot more complicated when you add in website traffic, multi-channel offerings, and the like—but that’s what marketing analysts worth their salt are for. If you want to truly stand out from the pack as a marketer, you’ve got to think more like a financial advisor than a social media influencer. Those impressions may be mighty impressive, but what did they add to the bottom line? If you can find out, then the gold mine of marketing may just be at your fingertips, poised above the great calculator of truth.