In January 2020, Google announced that third party cookies—essentially, small files or bits of code that websites send to your devices in order to monitor you and remember certain information about you—would cease to be supported on their web browser Chrome by 2022. Other browsers have done this already, but it’s raised attention because in this space, as Google goes, so goes the world.

The promise of digital advertising is, at its core, more precisely targeted, better attributed marketing investment. As advertising has moved more and more online over the past twenty years or so, the assumption has been that the ability to target the right people with the right message at the right time means better results for less money.

But that relies on being able to identify and target individuals based on their behavior. More recently a tug of war has developed between consumer privacy advocates, ad tech, and marketers. Everyone has good reasons behind what they’re doing, but they are at odds because it’s impossible to effectively market online without knowing things about people, and those people are rightfully skeptical about how that data gets used.

This is why, whether you’re a seasoned digital marketer or an executive who really only wants to know whether marketing is working or not, you’ve probably been hearing about “cookies.” So let’s cut through all the noise and get to what matters.

Who are we talking about: the players involved

Honestly, part of the issue is that when we’re talking about cookies specifically or data privacy generally, there are a wide range of actors involved, and as we mentioned before, their interests are often not aligned. First and foremost, there’s the user. Many people have concerns about how data is gathered and protected in the modern digital environment, but many also want the benefits that emanate from service providers’ ability to know who we are and what we’re doing online. We’ll talk a little bit more about this later, but it makes sense—I generally don’t want people to know everything about me, but it is nice not to have to fill in my password every time I log into a website.

On the non-user side, the actors break down into a few camps:

- Ad tech

- “Ethical” tech

- Industry groups

- The government

Ad tech

These are the demand-side advertising platforms—the people with the ad inventory for sale. And it’s an incredibly lucrative business for them. In a year, Google generates about $150 billion in ad revenue; Facebook brings in about $25 billion.

As such, it should be pretty obvious that demand-side platforms are not incredibly keen to see the industry fiercely regulated, whether that’s for privacy concerns or anything else. The people who are driving the revenue are not going to build an ecosystem wherein they can’t drive that revenue.

“Ethical” tech

Plenty of businesses in the tech space end up touching on these data privacy concerns without actually directly participating in the ad ecosystem. Some of them have taken a stand on the issue—Mozilla’s Firefox and the VC-backed Brave are examples of browsers that are particularly oriented towards solving online privacy issues. Apple, also, doesn’t have a revenue stream from digital advertising, so they’re able to position themselves as privacy-first.

Looking at this from the human perspective, it’s great. Things like iOS allowing users to opt out of data tracking and “Mail Privacy Protection” attempting to neuter email marketing are positive signals to consumers that this is an issue that is getting attention. On the other hand, Apple’s a business, and they aren’t doing this altruistically (at least not completely). It’s also brand positioning, allowing themselves to differentiate from competitors like Facebook and Google.

This is probably where the most (for lack of a better term) resistance against the ad tech powers exists right now.

Government and industry organizations

Here we’re talking about professional organizations in the space and government attempts to regulate online advertising and data collection. On the professional side, “watchdog” is probably too strong a term, but groups like the Interactive Ad Bureau (IAB) and Association of National Advertisers (ANA) are obviously going to have opinions on the subject.

And anyone who has worked in the industry in the past five years will be familiar with some of the new government regulations that have come through in that timeframe. One of the things about advertising online is that no matter where you’re personally located, chances are you’re going to need some knowledge about regulations around the country and around the world. After all, digital ads can be served anywhere from anywhere—we’re not talking about a billboard on the side of a building. The European Union’s GDPR, Canada’s PIPEDA, and similar legislation in California and Virginia have all tried to push back against data collection, while the Federal Trade Commission has also tried to do so with less success.

These governmental organizations are really the ones who can have an effect; whether the political will exists to successfully do something remains to be seen.

A data privacy sea change

Over the past few years, public interest in data privacy has grown a ton, partly due to a number of pretty high-profile data breaches. Because of this, there’s been a groundswell of support for measures to increase the protection of data that corporations are collecting, and those corporations have been more or less forced to act because of that public pressure. For example, Apple’s latest iOS includes the option to opt out of allowing apps to track your activity across the web; 94% of users have opted out.

But a lot of the actors who are taking action, as we said before, are not the same ones who are doing the advertising. Apple doesn’t have a vested interest in the “other side,” so to speak, so they can lean hard into privacy while everyone else is trying to find their place. For those of us who do rely on digital advertising for our livelihoods, the challenge is to find a way to meet consumers in a way that’s respectful of their privacy while also still finding enough information in order to properly target and broadcast ads to the people who are looking for the goods or services we provide.

This isn’t going to end, probably. Ad tech is still gathering data, and that’s not going anywhere. There’s too much money in the field, and honestly, despite worries about data security, a lot of users want it. We’ve been handing over data to Facebook and the like for years in the interest of a better user experience, and more content that matches what we’re looking for.

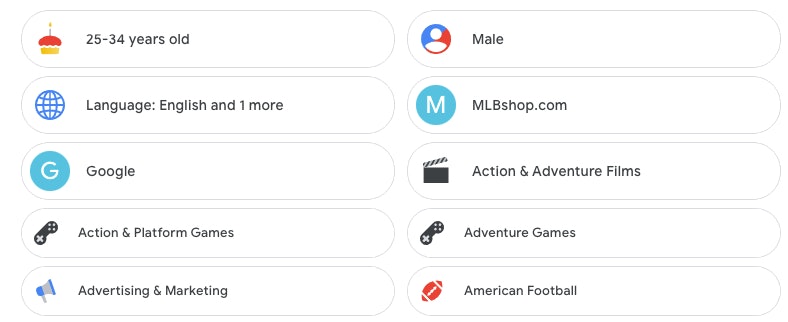

Why yes, I do like many of these things.

More money is being spent on advertising than ever before, and more money is going towards digital ads than ever before. And after the changes we all had to make last year, making us more “online” than ever, it’s unlikely that’s going to change.

Users care about how their data is used

When we talk about people gleefully handing over data to the internet, we’re not really talking about the life-changing stuff, or the things that bring Orwell’s 1984 to mind. There are really two categories of user data floating out there—one that we’re all pretty much cool with sharing, and the other we’re very much not. The reactions people have depend heavily on what the data is, and how it’s being used.

The Netflix model

When you watch a video on YouTube, it knows what video you watched and it remembers that. Then it looks at other people who also watched that video and others like it, and it examines what they watched next. That all goes into YouTube’s algorithm soup and the finished product is your “what to watch next” queue. It figures out what other stuff you might be interested in and tries to show it to you, killing two birds with one stone: it improves your user experience and makes you like YouTube more, and it keeps you on their site longer. This is the reason why after I watched five Historia Civilis videos, I found the Invicta channel and fell down a rabbit hole of videos about policing and law in ancient Egypt.

Spotify does this, Netflix does this, pretty much every avenue through which one consumes media online does it. And we love it. People adore the smart playlists that Spotify conjures, and because of that they’re willing to pay the price of sharing a little data.

But honestly, I don’t care whether the world knows what I watch on YouTube (obviously, since I just told you unprompted). What about the stuff I do want to keep secret?

The Wells Fargo model

So obviously plenty of the data that’s being collected is not that benign. I’m pleased that Netflix knows to tell me that the new season of I Think You Should Leave dropped, but I’m a little less enthusiastic about the number of sites that know my credit card information without me having to type it in. These are the things that we do not want other people to know, because it makes our money and our livelihoods (and sometimes even our lives) less safe.

There’s a lot of legitimate concern about things like credit card history, medical information, home security logs and video, and even our location data. In the past, it was possible to target users’ location precisely enough to serve them ads when they’re in a competitor’s waiting room. That’s no longer the case, and that kind of thing is probably never coming back.

And as marketers, data like that is honestly not necessary. That level of precision does give us more information than, say, knowing what state or city someone set as their home on Facebook. But when we’re targeting a Facebook ad, do we really need to know the exact cross-street our audience is sitting at? No, knowing they’re from Indianapolis or Carmel is enough to get the job done.

Why should marketers care?

That’s a very good question. Why do cookies matter in 2021? Why should marketers from the C-suite all the way down to entry-level digital interns care about what Google is doing to their web browser? The answer’s pretty simple: the death of cookies means it will be harder to know who’s doing what online, and when our ability to identify and target an individual changes, our effectiveness changes. And while, as I just said, this is not going to completely kill our ability to market effectively, these changes are going to force each ad dollar to do more work.

The tighter the curtains are drawn in front of who you’re marketing to, the harder it is to know who they are and what they’re looking for, and that means it’s harder to deliver what they want when and where they want it. And that means your cost per lead goes up, and your overall lead volume might change (depending on attribution windows) because giving credit to platforms will become more difficult.

In 2021, most marketing is, in one way or another, digital marketing. Tracking these trends is important for setting goals, it’s important for assessing performance, and it’s important if you want to make sure you’re putting the right money in the right places. Ignore what Google and its competitors are doing at your own peril.

NOTE: This blog post is adapted from a talk delivered by Element Three’s Business Development Manager Joe Mills, Senior Director of Web and Digital Strategy John Gough, and Associate Director of Digital Media Lynsey Johnson.